“In remembering, there is always present to the soul

the result of some past operation, and the soul acts on that result,

as on a new object. The soul has its being in eternity, but lives in time;

and the ideas of past and future are not derived from the relation

of the facts of memory to the soul,

but from the relation of those facts among themselves.”

~ William Batchelder Greene, The Doctrine of Life (1843)

Three weeks ago, I made my second relocation in the last nineteen months, all the while working full time. The August 2022 move had to be made, under the duress of the evacuation of the abruptly sold building I’d lived in for 37 years. The recent move had to be made, under the duress of intensely oppressive conditions which were unaffordable. The region continues to be plagued by the misery of a protracted housing crisis. My search essentially took two years of scouring, answering ads, pleading for leads, and traipsing through dozens of hovels. I’ve also been trying to assist others in similar straits. I’ve seen for myself that southern Maine is replete with community leaders and officials who cannot (and will not) relate to the obvious crises reported every day in the news. It’s been a continuing adventure through a paralytic universe of tone-deafness. Now I’m trying to connect my better contacts into some sort of helpful and needed community network. I’ve learned how the able are unwilling and the willing are unable.

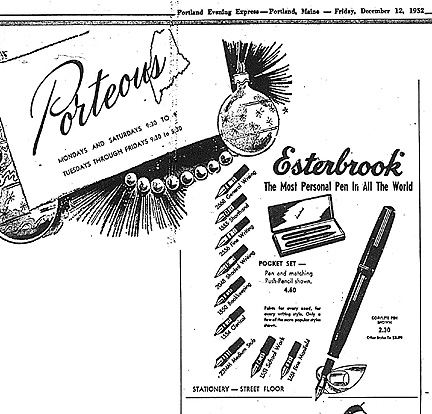

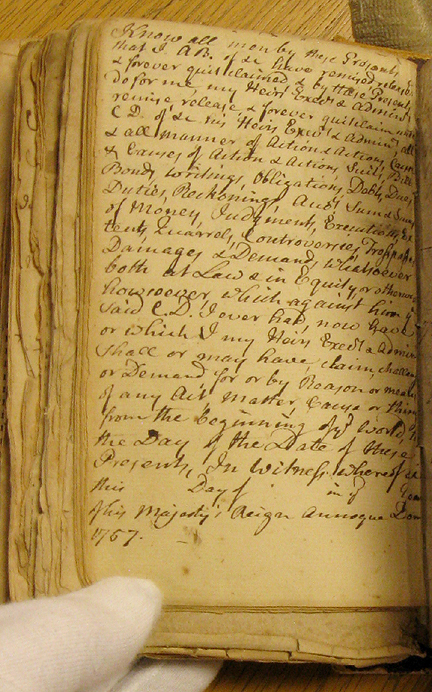

Below: How a bookbinder relocates.

Amidst such anxious times, there’s a shelter in the storm for which to be grateful. Discovering a place and quickly moving in winter amounts to an unusual scenario for this area. My elation at finding a good way out of a bad situation generated its own traction gear, powering me through muscling the move and deep-cleaning both the newer and the former apartments. The season-that-was lasted nineteen excruciating months, devouring more than two-thirds of my earnings. There was nothing else to be found at the time. Now that episode is past; enough said here about numbers. Through the crucible, I could not have guessed at its duration, having to depend upon a housing market as feeble and fickle as the job outlook. But surely I know enough to be thankful. I mailed my first rent check in a thank-you note.

All along, I knew enough and was determined to hasten the end of the previous tenure, and by grace I did it. Now in the aftermath, I’ve observed in my journal entries that healing takes time. It cannot be hurried, no matter the need and the eagerness. My tendency, especially with work projects, is to pursue conundrums and deadlines until appropriately vanquished and tested. Healing is quite a different matter: it must run a natural course. Acclimating to a different living space (is it presumptuously daring to say “home?”), the crosstown neighborhood, and a new commute, cause me to reconsider the meaning and worth of temporal things. The previous space was so forbiddingly cramped and loud, I unpacked only books and clothing, leaving the rest in transparent totes I carefully labeled that were stacked around me. Now, I’m gingerly unwrapping possessions I haven’t seen since packing them up two years ago in the West End. This is the unearthing of buried and migrated treasure.

Accompanying the nostalgia of again wearing knitted scarves made for me by my grandmother, and sipping coffee from bowls I’ve carried back from Paris, the new place is coincidentally around the corner from where I lived as an art college student. “Rejoined” with a familiar neighborhood which I’ve always appreciated, I’m amusingly making note of various items I’d had with me during those school years which have “returned” with me. As examples, my desk and my bicycle have “been here before.” Revisiting these streets, I’m effortlessly remembering people and places I knew back in the 1980s, with impressions that have lived on to this day. Indeed, “When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.” Yet, still, I speaketh much like I didst when I was eighteen years old. Out on a neighborhood stroll, one recent evening, I mused about what would transpire if my present-day self met my undergrad-student self on this shared intersection. Cause for great conversation, but it will have to suffice as journal entries across time.

“Are you really me, sir?”

“I think so, man. In fact, I think I still look like you.”

Oh, the trouble from which I could’ve saved myself. Continuing my walking, I remember businesses that used to be in some of these luxurified storefronts. The street patterns are as I left them. I’m now becoming acquainted with the No.9A and No.9B bus drivers, after a year-and-a-half with the Congress Street No.1 bus drivers. More new people I’m inviting to the library. “How you doin’, Mister Archivist? Find anything good today?” Always. Between the lurching bus rides and the work shifts, there are plenty of interesting reminders for me, right nearby. How temporal is this residency? I’m noticing myself shrugging off such thoughts, knowing how much effort and expense went into this move. Now out of the former place, it continues to astonish me to realize how egregious it was, and how thankful I am to have survived. There wasn’t a single evening of peace in there. But now it’s past. Let the healing really take effect.

After moving all I could with my car and a rented van, I hired professional movers for the heavy boxes of books and the furniture, to complete the job. One of my former neighbors saw the big vehicle beeping its reverse motion, and asked me the obvious: “Moving day today?” “Better than that,” I replied, “it’s Liberation Day.” True to my word in these pages, my childhood Felix the Cat rode shotgun with me for one of the last carload runs across town. As promised, I found a better place. And I thanked my praying friends at the Saint Anthony Shrine, in Boston. The building here has a wide front porch that nobody else uses. It’s ideal for writing, studying, and fresh air; a great perch for increments of healing.

I’m reminded of the one episode, back in 2015, when I had to deal with a serious back injury. The severity of the pain was such that each motion I’d previously taken for granted was accompanied by wincing and gasping. I made as many medical and therapeutic appointments as possible, tenaciously intent to be done with pain so disruptive I had to tie my shoes while lying on my back. The healing process could not be hurried, so I was told, and took about two months. On the first day without any noticeable pain, I elatedly took a meandering bicycle ride. It was amazing to me. Naturally, I returned to taking my flexibility for granted, though since then I’ve become adept at healthful stretching- not to mention wise ways to move heavy objects! The new dwelling place is in an old, creaky building- but it’s tidy, quiet, and gets a lot of sunlight. My general sense is that of a restart. Between work commitments, I’m enjoying the porch as much as I can, and look forward to the more verdant months. Healing is taking time, but I know where all the totes are that house my writing materials. Everything is labeled and ready for use.